Not a Friday Open Thread (about Hades)

This started out as a Friday Open Thread about how I finished playing Hades, and ended up being an essay partly about Hades and partly about Hadestown and partly about Palestine. The latter may be upsetting — goodness knows it upsets me a lot — so feel free to stop reading at that point if you just want my feelings on the game and/or musical phenomenon.

Dear Friends,

I “finished” playing Hades today — by which I mean, I reached the credits screen — by which I mean, I battled my way out of Hell, and lived.

I’m a swirl of emotions over this, and the friends with whom I usually share these exploits and their attendant feelings are friends I communicate with via Signal, which is down today. And I’m on Twitter hiatus. So I’m sitting here, writing to you from a place of quiet astonishment at how much communication we have at our fingertips daily, constantly, and how it shapes our thoughts and connections, and how something we take for granted becomes a problem to solve.

Signal is down because of an enormous influx of users from WhatsApp; that influx is due, from what I can tell, to misinformation surrounding WhatsApp’s new privacy policy. (“The furor over WhatsApp’s privacy changes is bitterly ironic, given the company’s struggles with misinformation on its service,” says the NYT article linked there). There’s a strange and terrible poetry to a communication service haemorrhaging users due to the kind of miscommunication they’ve been uninterested in managing internally — and a worse poetry to that miscommunication taking down a totally separate service. A lesson, of some kind, about putting out fires before they spread, whether or not your own home’s the one presently burning.

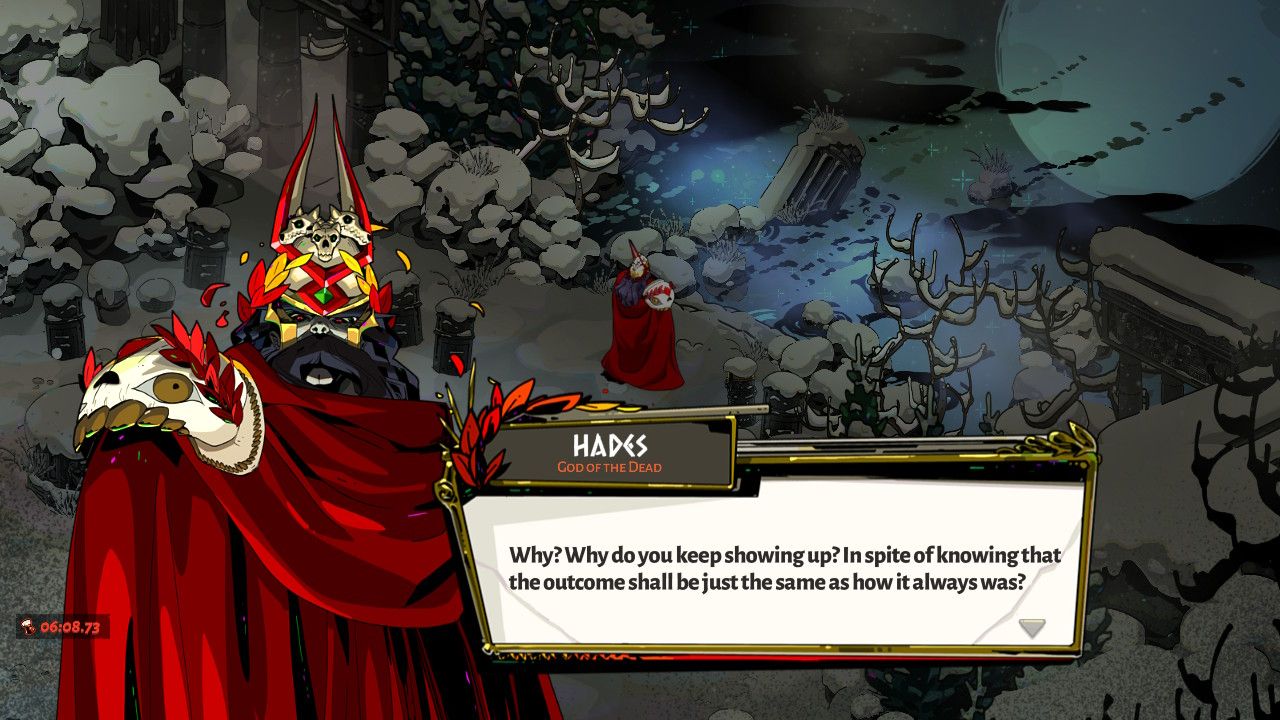

Hades is, in some ways, a game about communication and its (quite literal) pitfalls; a game about well-intentioned deceit, and fumbling honesty, and rigorous concern with ongoing consent. It’s profoundly tender, and astonishingly kind; it’s surprisingly thoughtful and beautifully designed. If my Switch Lite were at all integrated with other systems I’d share some of the dozens of screenshots I’ve taken of moments that have moved and overwhelmed me, but the one I can’t get away from right now, having finished, is this one — where Hades, helmed and armoured to strike down his only son and prevent him from escaping the Underworld, asks

“Why? Why do you keep showing up? In spite of knowing that the outcome shall be just the same as how it always was?”

There’s a moment I’ll never forget from the off-Broadway run of Hadestown. It was my second viewing at the New York Theatre Workshop in May of 2016. I had, by this point, listened to the concept album hundreds of times, always feeling there was something slightly slipped, slightly missing from the end — that it came too abruptly, that an old story reasserted its shape too suddenly on the fervent, anguished newness of Anaïs Mitchell’s transformation of myth. But the staged show was different. A handful of lines spoken in Chris Sullivan’s weary, generous voice:

'Cause here’s the thing (about tragedy)

To know how it ends

And still begin to sing it again

As if it might turn out this time

I learned that from a friend of mine

I cried violently. I cried so hard I couldn’t see, which, with the house lights up and the coda still taking place, should have been embarrassing, but I didn’t care. I cried so hard that Chris Sullivan’s eyes met mine and he briefly broke character, or at least bent it in my direction, in a way that I’m choosing to remember as touched, or moved, by the impact the show and his role in it were having on me. I remember a melting gentleness in his regard, a drop in the shoulders, a touch of a sad smile, distinct and separate from his performance as Hermes.

To know how it ends, and still begin to sing it again, as if it might turn out this time.

That this is the sentiment in two separate contemporary imaginings of this particular set of myths makes perfect sense to me. Our lives are so brief, and the world is so vast, and we somehow contain each other. This is why we make families. This is why ancient Greece imagined winter was born of a mother’s grief over losing her child.

(The first time I used Demeter’s Call in Hades, I choked up: an expanding swirl of ice-blue damage and the cry, I will take everything away)

This is, of course, partly about the pandemic — about repetition, about hope, about surviving the winter and longing for spring. Lately my evenings with Stu have settled into a comfortably recurring shape: we have a TV for the first time in four years, and there’s a lot of programming he’s interested in watching but that’s too tense or upsetting for me. We want to hang out together, though, so he watches while I sit nearby and slaughter bone hydras, and it works far better than it should. Tonight, Stu was watching a 2020 documentary called Mayor, about the realities of municipal governance in Ramallah, and knowing how completely skinless I am about anything to do with Palestine, he was especially solicitous about whether I wanted to be in the same room with it.

It was a strange experience. If I wasn’t watching the screen, I was hearing Arabic that sounded like my family’s; if I was watching the screen, I was either laughing at what the subtitles were missing or frozen in furious grief before I remembered I could be stabbing Theseus in his big jerk face instead. But there it was, ultimately, this killing familiarity: the same talking points, the same loss, the same grief, the same enormous, indecent, unbearable endurance that I was raised in the knowledge of. Ramallah can’t treat its own sewage without Israel’s approval, and Israel isn’t in the business of approving anything that makes Palestinian life easier. There’s a horrible joke in here, somewhere; it took them fifteen years to approve a cemetery.

(Palestinian existence gets styled, in fascistic talking points, as a “demographic threat” to Israel; inexplicably, in the face of demolitions, checkpoints, raids, Palestinians will insist on having children. To know how it ends, and still begin to sing it again—)

Part of me thinks it’s indecent to connect Hades and Palestine; a game on the one hand, and on the other, a geopolitical reality that has defined almost the entirety of my life. But we exist in a world where geopolitical realities are treated as games by the worst of the world, who overlap almost perfectly with its most powerful; the documentary observes, for instance, the impact of Trump’s arbitrary naming of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel in 2017. Why shouldn’t games — like any art — give us the means of articulating and managing our grief?

I didn’t meant to talk about Palestine in tandem with Hades, but the Fates decreed otherwise. I never mean to talk about Palestine, or Lebanon, or Syria, but they’re always there, a red river running through the house of me, and any attempt to navigate away from it by labyrinthine means only lands me back in its currents. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all the games and books I love with every fibre of my being are about the fierce grace of endurance, the active, deliberate choice to love, and play, and begin over and over despite knowledge, despite horror, despite everything.

I reached the end credits of the game as the documentary concluded. In the game, there was a boat, and a river; in the film, there was a fountain, and light. In the game, the music took on a refrain that sang “in the blood, in the blood” and in the film, Andrea Bocelli duetted with Sarah Brightman in “Time to Say Goodbye”. They wove in and out of each other — everything a game could be, and a fountain could say, with everything I couldn’t. The train may stop, but the line goes on.

It’s a very good documentary, and a brilliant game. I recommend both.

See, Orpheus was a poor boy

But he had a gift to give:

He could make you see how the world could be,

In spite of the way that it is

Can you see it?

Can you hear it?

Can you feel it like a train?

Is it coming?

Is it coming this a-way?

Member discussion