WisCon Guest of Honour Speech

This is the speech I wrote and delivered at WisCon in 2017, when I was Guest of Honour alongside the magnificent Kelly Sue DeConnick. I was holding off posting it for a long while because I was told that video of the speech would be made available, and I wanted to share that instead of the text alone; I also think I spoke some things off the cuff (like thanking all the people who helped make the con amazing for me, dear gods please let me have actually done that) or hastily scribbled them on to a print-out I no longer have, so this is not the most accurate version of what was spoken in that amazing room where hundreds of people spontaneously sang songs from Steven Universe with me and we all cried and shouted together and closed a gorgeous circuit.

A year later I still don't have the video, but certain conversations invoking Wiscon as somehow incompatible with broader fandom have really pissed me off, and I want to share this speech, which was the culmination of the love and gratitude I feel for that convention and some of the reasons for it.

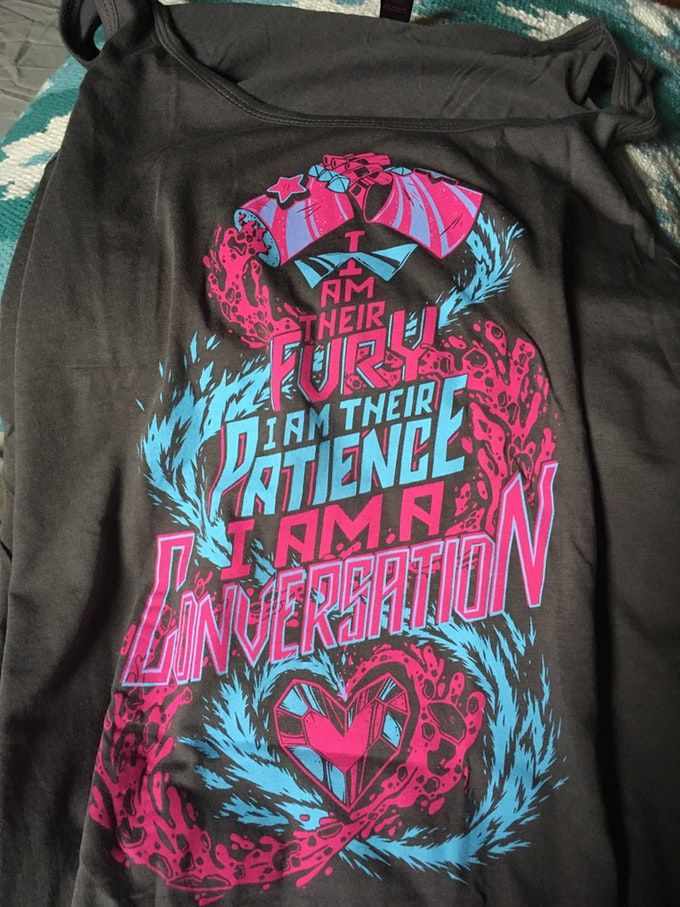

(The image on this post, by the way, is of a tank-top my husband got me as a birthday gift. The design is by Unicorn Empire Prints but it may have been a limited thing.)

Here you go.

***

I love talking.

If I have a super power – besides waking up an hour before my alarm goes off no matter how early I set it, or always choosing precisely the right size of Tupperware for leftovers on the first try – it’s talking. It’s my favourite thing. When I was little, four or five years old, my parents would gently warn our neighbours not to give me an opening, because I would, quote, “talk them out of their day.”

Without really thinking about it too hard, my capacity to communicate has become a core part of my identity. Again, when I was little – but growing, you know, little but the eldest of four children – my parents trained me to be, in their words, a diplomat: it was up to me to break up fights between my siblings, to stay calm, to not lose my cool, because, as we say in Arabic, “al wa3a al kabir be sa3 al wa3a al zaghir” – the big pot carries the little pot. I was the big pot among my siblings, so I was expected to carry them – through games, through disagreements, through translating their needs and desires to each other.

I was not great at it. I was often impatient. I had my own needs and desires – most of which were to be left alone to read books. But I like to think I got better, with practice – and I learned a lot about myself.

It should come as no surprise that my favourite media, my deepest, most heartfelt fandoms, favour great talkers. Hamilton – “Oh was I talking too loud? Sometimes I get overexcited, shoot off at the mouth” – Doctor Who – the triumph of intellect and romance over brute force and cynicism, talking a mile a minute while staring down the barrels of guns, his enemies awe-struck, bemused into listening – but deepest of all –

wait for it, wait for it, wait –

Steven Universe.

We are the crystal gems. We always save the day. And if you think we can’t, we’ll always find a way.

That way they always find? It’s talking to each other.

Unlike the Doctor, who monologues and pontificates, Steven does more than talk. He listens. He asks questions. Steven has conversations.

This, here, is the core of what I want to talk to you about – and ironically it’s also the great failing of this speech. Because I’m up here talking at you, but what I want to do is have a conversation. I built this speech out of conversations I had for a year, leading up to this convention; I built it out of conversations with friends here at the con, over lunches and dinners and private freak-outs in my room. I want to imagine us sitting around a table that somehow contains all of us without us needing to shout across distance to be heard, where we can each hear each other clearly and perfectly and respond in kind.

It’s possible we may one day invent a technology that enables us to do that. It certainly isn’t the internet.

But let me dwell, first, in Steven Universe, and the history of my watching it, because it’s rooted in conversation.

Once upon a Readercon I was on a panel with Nicole Kornher-Stace and Navah Wolfe about drift compatibility. We were talking about the usefulness of that metaphor from Pacific Rim – this concept that allows at least two people to pilot an enormous robot and punch extra-dimensional sea monsters in the face. This, we felt – years before punching monsters in the face become disturbingly topical – was the metaphor of our times: drift compatibility was the magic of friendship, of deep intimacy and trust, of family bonds, that enabled us to accomplish great things we couldn’t do on our own. No one can pilot a giant mecha on their own – but two people, three people, sharing the neural load between them, can.

On that panel, Nicole said this reminded her of Steven Universe – a show neither of us had yet watched. She bit her tongue and said, I don’t want to spoil anything, but go watch it, you’ll understand. So I did. And I was hooked.

The first episode of Steven Universe to make me cry is called “Giant Woman.” It’s the episode that explains the concept of fusion: the gems – beings whose bodies are manifestations of light – are able to fuse: they dance together, and in a moment of profound intimacy they meld their bodies into each other and become a completely different gem, stronger, bigger, more than the sum of their parts. Pearl and Amethyst merge to become Opal – but only in times of great duress, because Pearl and Amethyst can’t stand each other. Steven sings to them, all I want do / is see you turn into / a giant woman / (a giant woman!) / all I want to do / is see you turn into / a giant woman.

The part that made me cry was later in the song, where Steven himself says but if it were me, I’d really want to be, a giant woman.

I was completely unprepared for the sight of a small boy loving and admiring his female guardians so much that he wanted to be them. I was thoroughly unprepared for the queerness of that statement, the love, the tenderness, the pure perfect joy.

But there’s a dimension to it, to fusion, to Steven’s desire to be a giant woman, that doesn’t get explicitly stated until much further along, in an episode called “Jailbreak.”

In “Jailbreak,” a Fusion gem that was broken apart into two separate people manages to reform right before battling a terrifying adversary. She does so while singing:

“I know you think that I’m not something you’re afraid of,

because you think that you’ve seen what I’m made of

But I am even more than the two of them,

everything they care about is what I am

I am their fury, I am their patience, I am a conversation.

I am made of love

and it’s stronger than you.”

I am their fury. I am their patience. I am a conversation.

This broke me open in ways I haven’t been able to stop thinking about in the context of women, and feminism, and the communities to which I belong. I have been writing this speech in my head for a year in the hope of getting something right in the speaking of it. I hope you’ll bear with me.

*

When I heard that line, I thought of how often women are denied conversation with each other. I thought of the Bechdel-Wallace test, of this diagnostic tool we have for measuring the distance between our reality and the representation of it. I thought of how vast is the gulf between my experience of talking – with my female friends, with my sister, with my mother – and the representation of women talking. Women talk too much, we’re told, if they talk the same amount as men. Women have unpleasant voices, we’re told. Women are shrill. Women chatter, women have nothing of substance to say, women scold, women whine. For hundreds of years literature has been telling us that a virtuous woman is a silent woman. Intercourse – a word for speech – comes to mean a very specific kind of sex that is both the only socially sanctioned kind and, curiously, the kind that brings women to ruin. In 1653, Margaret Cavendish wrote words that could have been written today: “[W]e are shut out of all power and authority, by reason we are never employed either in civil or martial affairs, our counsels are despised, and laughed at, the best of our actions are trodden down with scorn, by the over-weening conceit, men have of themselves, and through a despisement of us.”

Plus ça change.

But as much as the world has been trying to shut women up for centuries, to curtail and mitigate our voices in the social order, in democracies, in civil society – more disturbing to me by far is the extent to which the world is organized to prevent us from talking to each other.

In 1845, Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote, “I look everywhere for Grandmothers and see none.” This sentence has been haunting me since I first encountered it in an undergraduate course in English literature some 15 years ago. At first, I thought, how sad for Browning, and how lucky for me to live in a more enlightened time!

I had no idea who Joanna Russ was until she died. The woman who literally wrote the book about how women’s writing gets suppressed had been hidden from me. Until I came here, to Wiscon.

Or Naomi Mitchison. Dear gods, Naomi Mitchison! Naomi Mitchison was a contemporary of Tolkien and good friends with him. She read and commented on Lord of the Rings in manuscript. She wrote over 90 books and lived to be 101. She travelled the world, she was Scottish nobility, she was an ardent advocate for birth control in the 60s, she was the mother of seven children, she had a happy open marriage and several lovers, James Watson dedicated The Double Helix to her! She died in 1999, when I was 14 and reading anything with pages – and I had never heard of her. I wouldn’t hear of her until, again, I came to Wiscon, and met Karen Meisner, who gave me a copy of Travel Light, recently reprinted by Small Beer Press, who, by the way, I also first heard of at Wiscon.

This convention has changed my life in so many ways. This convention was the first to allow me on to a panel – one about women in speculative poetry, nine whole years ago in 2008. I sat nervously in the Sun Room Café with my dear friend Jessica Wick as she helped me prepare me for this enormous responsibility. I wanted to be worthy of the other panelists. I wanted to be worthy of the audience. I wanted to be worthy of the topic, to be worthy of the convention that I felt had entrusted me with something precious, this responsibility of carrying on a conversation.

This convention drew me into an awareness of beautiful, hard, necessary conversations, and showed me how much feminism – something I thought of as a monolith, then, a common sense principle – was in fact a tapestry of conversations, many of them very difficult, many of them struggling to find a common language to address the very different problems we face at the intersections of race, class, disability, queerness, immigration status, indigeneity. This convention – by being, explicitly, a place where women come together to talk, to share histories and realities and speculations, to challenge each other and dream together of better, more just worlds – taught me most of what I know about these things.

I want to make you feel how precious that is – and how powerful. Because I am terrified of losing it.

*

We exist at a time when technology has made it easier than ever for us to talk to each other, and harder than ever for us to have conversations. We exist at a time when the internet has been colonized by capital, where every article plays a clickbaity game of “Let’s you and her fight.” We exist at a time when we’re encouraged to see conversations as slapfights, where titles read like mockeries of conversation: “No, So & So, You’re Completely Wrong About the X-Men” – “Yes, Such & Such, Wonder Woman is in Fact Feminist.” Why do we do this? Why is conversation forced into confrontation, into a battleground of winners and losers? Why do we talk about “losing” an argument instead of learning a truth?

To be perfectly honest, I think it’s a con – and not the good kind, not what we’re attending. A Mr. Wednesday con. A grift. A trick. A new, insidious way for the evil systems of our societies to continue preventing us from talking to each other, learning from each other, and loving each other.

Let me give you another bit of wisdom my parents taught me. This is from Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan, First Caliph of the Umayyad dynasty. I do not apply my sword where my lash suffices, nor my lash where my tongue is enough. And even if there be one hair binding me to my fellow men, I do not let it break. When they pull, I loosen, and if they loosen, I pull.

This, too, is a conversation. This, too, is a fusion of fury and patience. That single hair can be a bridge we walk across, towards each other.

We don’t have to agree with each other to converse. But we have to listen. We don’t have to bite our tongues, keep calm or be polite. But what I wish we did more was recognize when we are the big pot – when we have the wherewithal to meet fury with patience, to loosen when someone pulls, to keep our hair in each other’s hands.

White supremacy. Neo-Liberalism. Settler-Colonialism. These are the vast, almost unfathomable monsters of our time, burning our skies and salting our earth.

But we can be giant too.

*

To me, a conversation isn’t a pitched battle between positions. It’s a journey you set out on with a person you trust, not knowing where you’ll end up. And please, please don’t hear what I’m saying as a call for civility, an appeal to tone arguments, a beleaguered cry of why can’t we all get along?

I know perfectly well why we can’t all get along.

Sometimes I think the metaphor of a glass ceiling is wrong, is misleading. It’s not a ceiling – it’s a valley, and we’re all clawing at the walls trying to think of ways to climb out. We can see through this glass valley to the world beyond, the world that’s denied us, and the walls hem us in against each other, and some of us are on top of others trying to climb out, and others are on the bottom hurting harder than ever from the weight of those trying to climb out, while the shape of this valley tells us that climbing out is the only thing to do.

But it’s not. It’s hard, hot, painful, difficult work – but I have to believe that we can work together to smash the valley walls to sand. I have to believe that we can fuse into a giant, magnificent woman so huge we can stride out of the valley together and crush it beneath our heels.

*

Once upon a time, my seven year old niece asked me to tell her a fairy tale. I wanted nothing more than to do so – but what crowded my mouth were stories of women isolated, women won as prizes, women hating each other, step-mothers at their daughters’ throats. I was violently struck by how I knew stories full of firebirds and golden apples and djinn but somehow, more impossible to conceive of than all of these was the notion of two women talking to each other about something other than a man.

I wanted to tell her better stories.

So I made one up. I took two fairy tales and I made them have a conversation. I fused them together to try and make something that was more than the sum of their parts. I took one woman who was forced to walk in iron shoes and one woman who was forced to sit on a glass hill and I had them meet each other, speak to each other, tell each other their stories. And, more crucially still, I had them read each other’s stories back, against their grain – I had them resist, get angry, find fault with each other’s poisonous narratives.

I had them rescue each other.

Because this is what it means, to me, to talk to each other in good faith, to listen to each other, to meet fury with patience. Because when we do those things, we change the fucking world. We pilot enormous robots and punch Nazis in the face. We fuse into giant women who are more than the sum of their parts. We become grandmothers and grandaunts and fairy godmothers, we pass on knowledge and protect it, we hold on to each other’s hair and braid it together across decades and borders and bodies and no power in the world can stop us.

In an article titled What Persona Is Still Teaching Us About Women Onscreen, 50 Years Later, Emily Yoshida wrote about “the terrifying magic of two women in a room, talking. And there’s still so much of it we haven’t explored yet.” I want us to explore this together. I want to set out on this journey with you, holding hands. I want to give you my patience and trust that you will listen and bear my fury, the fury I feel all the fucking time lately. I want to stand with you against the giant monsters of the world and shout lines from Steven Universe until we find a way to save the day. I want to stare down the vicious, hateful malice of the world and say we are their fury, we are their patience, we are a conversation. We are made of love – and it’s stronger than you.

Thank you.

Member discussion